Monika Savier presented this brilliant talk at the 2025 WAHO Conference in Abu Dhabi, and we are delighted to share it here in full.

Click here to listen to TheArabianMagazine.Com Podcast on different streaming services.

The loss of natural reproduction in Arabian horse breeding and the effects of modern reproductive technologies affect breeders and horses all over the world. In this respect, the opportunity to discuss the issue at the WAHO conference in Abu Dhabi is a fantastic opportunity to highlight the problems. It is a reminder to fellow breeders that Arabian horse breeding should also meet sustainability requirements to preserve a healthy breed for the future. Mr Basil Jadaan, Syrian breeder and member of the WAHO Board, told me in an interview many years ago: “The horses can’t talk. You have to speak for them and write what they would say…”

Do we consider the natural reproduction and the effects of ‘assisted reproduction technologies’ (ART) and breeding methods from the perspective of our horses? The contrast between the original natural processes of reproduction, from which this noble breed has emerged, with the widespread use of today’s reproductive technologies is vast. Of course, reproduction technology can be a great help in special cases, but as an industry, it has greatly increased the costs of breeding and in some contexts it is counterproductive. Somewhere along the line, the mental and physical welfare of the horses themselves has been almost totally forgotten.

For the past 100 years, the world has been changing rapidly, the consequence of this is that modern assisted reproductive technologies can now determine the course of our horses’ lives. Horse breeding has become more expensive but not necessarily more successful. No more ‘horses of the century’ have been born in recent years, despite science and modern technologies for improving breeding. Instead, our breed’s gene pool has narrowed considerably. What also falls by the wayside is the natural contact between stallions and mares, their communication and their libido. And that has its side effects.

When we talk about horses today, we reveal not only something about the nature of the animals and their breeding, but also about the society in which they live. Lifestyle, prosperity and self-interest have fundamentally changed the way we deal with the horses entrusted to us in recent years. Just a generation ago, responsible horse breeders would have retired a stallion that had low fertility and taken him out of breeding. Or a mare with a noble pedigree who does not want to accept her foal. Today, these cases are a welcome challenge for ART. And thus, these genetic problems are now spread around the world.

Surprisingly, modern reproduction technology is taken for granted. A shifting baseline has taken place in some countries whereas in others, resistance is growing in the interests of the horses and the question of economic sense.

When I watch the vets at my stud freeze the semen, and straws containing billions of sperm are suspended in nitrogen containers, I wonder how the Arabian horse has managed to successfully spread from the Arabian Peninsula across the continents for thousands of years, healthy and lively, without ultrasound, swab tests and hormone administration.

The decision of whether to allow artificial insemination and embryo transfer have been left to individual countries to decide. There are mandatory rules that have been in place for many years, stating that foals produced by any form of in-vitro fertilisation, gene editing or cloning cannot be registered in a WAHO approved stud book. They are difficult for the Registries to police. By readjusting a few important parameters in the rules and regulations, we can initiate changes.

Today, there are many owners of Arabian horses who do not know the real world of their animals, neither their social behaviour nor their communication with each other. The character of their horses, a truly important element, is unknown to many. They are investors. Their horses are kept in large training stables to be trained and mated. For these owners, the horses are often little more than collector’s items. They trust their experts, veterinarians and trainers, and usually leave the breeding decisions to them.

Experienced breeders know that by artificially interfering with reproduction, they are depriving the horses of an important part of their lives: the desire and joy of sexual communication. Who does not know from breeding practice in the past that mares did not show heat at all in front of certain stallions, although the veterinarian measured a 4cm large follicle? Meanwhile, reproduction has become an expensive problem area. In veterinary medicine, the background of these behaviours is rarely reflected upon, because the pharmaceutical industry, the food industry and reproduction technology take care of the problems themselves. Artificial hormones in every phase of the heat or as accompaniment and ‘protection’ of the pregnancy are standard today. Most veterinarians follow a protocol without considering the situation and condition of the mare individually and including it in the treatment.

The most common current husbandry conditions for stallions and mares – that require strict separation, stallion quarantine, and controlled breedings – can be traced back in many countries to national laws for the prevention of infectious diseases, a price we have to pay for the globalisation of reproduction, i.e. the shipment of semen.

Much has changed in the behavioural psychology of horses, and the reality at stud farms today shows that not only do breeders suffer from the cost explosion caused by artificial reproduction, but that stallions and mares have also had to change and adapt their lives immensely. So how do we make their lives better, from a horse’s point of view?

Just a reminder: if you are male and want to breed, you have to be nice! In principle, it has always been about one thing, at least for stallions: showing yourself, courting, convincing the mare… And finally, breeding. This is what makes the stallion charming and peaceful, quite unlike his reputation. In practice, he tries to get along well with everyone, as he never knows when an opportunity to breed a mare might arise. Yet to be able to behave in this way, he needs a minimum of behavioural options, exercise, hopefully the chance of turn-out on the pastures and at least an opportunity to see, smell and touch his mares.

In biology, there is the scientifically proven term ‘female choice’. This term refers to a mating system whose most important characteristic is the fact that in the animal world, the male must work for the mating. He has to perform. For example, he can sing particularly beautifully, or present himself in bright colours, perform dances or bring gifts – in every species, the male has his specific advertising behaviour to keep his competitors in check. He has to impress the female and convince her he is ‘the one’. The competitors are always the other male animals, which have to be defeated.

Stallions show their charisma and athletic bodies, accompanied by a lot of shouting, to be heard by the mare. They have to advertise themselves to be able to have sex, because females are choosy in nature, setting high demands and conditions.

“Female choice says that the reproductive strategies of the sexes are completely different. Simply put: males go for quantity and try to mate with as many females as possible. Females, on the other hand, go for quality and only mate with the best male. This is because reproduction is much more costly, time-consuming and long-term for them. So, the male must gather many around him, and the female must fend off many. One of the most important characteristics is that most males in nature rarely or never find a mate,” writes biologist Meike Stoverock.

Charles Darwin once wrote, “he who conquers, mates”, and the conqueror had to be not only strong but also intelligent to be able to take on the evolutionary challenges. Darwin called this principle “sexual selection.”

If a mare is to produce a good stallion, she must have a dominant role in the herd, intelligence, pride and composure to produce a confident son. A normal foal, raised with a submissive mother, is unlikely to feel any desire to fight for the role of a leading mare or stud stallion. Experienced breeders know that a timid mother produces timid foals, but a dominant lead mare imprints this character onto her foals, which is passed on for generations and, for example, creates the best conditions for a future racehorse. Trainers look for horses whose social behaviour in the herd shows the mentality of ‘better dead than second’. They are looking for those who will not let themselves be overtaken by the others on the racetrack and will always fight their way to the front, even when the situation is difficult.

Even if some behavioural scientists assume the stallion is the leader of the mare herd, observations of wild horses have repeatedly shown that the stallion has to fight for entry and his leadership role in the mare herd at the beginning of the mares’ heat period until the lead mare accepts him. Only then can it be said that he is the boss in the reproductive area, while the lead mare continues to take care of the important decisions in the general herd life. This includes the vital search for food and the early warning system of the mares with foals in front of a predator on the horizon.

There is a fine balance between the mating behaviour of the sexes, and even if the stallion is finally allowed to mate with the mares after a long courtship and with a great deal of posturing, he still must work for each individual mare.

In doing so, he has to be careful and inventive, because every mare is different and the mating act itself requires the stallion to recognise whether the mare is really ready, from a hormonal point of view, to let him mount her without fighting him off and potentially causing him serious injury. This forces the stallion to use his intelligence and charm to woo the mare, to convince her to succeed, and is an important aspect of his social behaviour and part of his behavioural code.

Today, for so many of our horses, the stallion no longer has to be charming to be able to breed, and the mare no longer has any decision-making power over the stallions. In fact, today’s stallions are sometimes rather difficult, even dangerous. They may no longer know natural limits; they lack the education from the mares and the realisation that they have to submit to certain conditions in order to succeed. As a result, they can develop not only health problems but also stable vices that are signs of severe mental stress. Instead of being able to advertise themselves, they wait for the vet with the artificial vagina. No self-promotion, no competitors, just delivering semen. The stallion may be famous, but sad.

The principle of female choice is also fast disappearing in today’s horse breeding. This had previously defined their reproductive cycles, able to decide at least to some extent whether or not to accept the advances of a particular stallion. But now the breeder decides, and the vet does his job and inseminates the mare – she no longer has a choice.

It has taken a long time for horse breeding to reach this present point of extensive de-naturalisation of the reproduction process. So, what was the trigger?

One of the technical innovations of the 20th century had a particularly significant impact on breeding and ultimately on the living environment of horses – frozen semen and, as a result, artificial insemination. At first only used locally, before too long the ability to chill or freeze semen and ship it worldwide was developed. Arabian horses became part of globalised markets. Semen could be bought and sold online, and unlimited storage in liquid nitrogen without an expiry date made it possible to send it across all continents. Now the semen came to the mares. This was certainly an advantage in connection with risky horse transport and an enormous gain for the stallion owners, who were now able to sell many more breedings.

With the increasing use of artificial insemination, an existential disadvantage for colts born of those breedings arose. From then on, they lost value everywhere. Before the widespread use of transported semen, we looked for interesting stallions that fitted into our breeding concept. We went to shows or visited them at their home stables. We took their temperament into consideration, and how they would complement our mares. Their sons could usually be bought for a reasonable price.

But with unlimited access to the semen of champions, mare owners choose to breed to those sires rather than buy their sons. Which, in some cases, also led to the market being saturated with their colts, so the breeder would discover that their market value was below their production costs. Unlike the breeders of Thoroughbred racehorses – their rules forbid anything other than natural covering, for very good reason.

While on the racetrack and in endurance sports, breeding selection is largely based on the athletic performance of mares and stallions, the selection of show horses and certain bloodlines is left to their own markets. On the catwalk of Arabian horse shows, we find perfect beauty, sometimes bordering on the unacceptable, because the functionality of the animals is subordinate to it. These winners share the market of good mares because their stud fees are too expensive to experiment.

Less fashionable stallions are often overlooked, so as a result, we also risk a reduction in stallion quality, because as the great breeders said before the turn of the century: ‘You need fifty young stallions to be able to select two-to-three top stallions that will advance breeding’.

As a result, the gene pool of our current horse breeding has narrowed. A look at a modern pedigree often shows a high degree of inbreeding, but far too rarely with a strategic breeding concept. Inbreeding is a tool to successfully implement our idea of breed type, which today means beauty, functionality and brand homogeneity. Inbreeding can also be used to successfully suppress bad genes. However, not everything that meets an ideal of beauty is also healthy for the development of the breed. Therefore, inbreeding should only be used up to a certain percentage and according to scientific criteria.

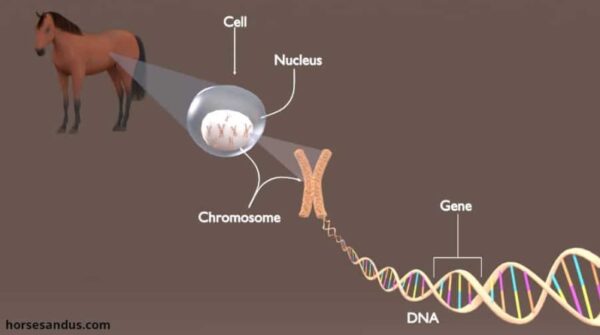

How did the already quite high level of inbreeding in Arabian horses come about? The genetic makeup of champions, whether on the racetrack or at an ECAHO show, is highly coveted and expensive. Using them in breeding is a status symbol for many. In addition, there is the hope of being able to repeat this success with their own mares. But it’s not that easy, because genetics is a broad field. Sons and daughters or siblings each have a very different genetic makeup, although parallels and similarities are often recognisable. The semen of champions is now used everywhere. More than 1,000 foals sired in his lifetime is not uncommon for outstanding champions due to artificial insemination and the shipment of frozen semen. Unlike in nature, these winning chromosomes spread all over the world. Many stallions, on the other hand, are hardly used at all. When the champions’ offspring are then mated with each other to consolidate the famous characteristics, the so-called popular-sire effect arises.

Genetic defects can now become dominant and homozygous, causing diseases that can be passed on genetically. You could match two beautiful, perfect looking show champions, neither of which show any physical or genetic defects, and yet their offspring can have a lack of type for the show-ring and inherit both conformational issues and genetic disorders. Why is that?

Luckily, nature has packed a second set of chromosomes into each working cell. This is how a functioning organism can develop from two blueprints of life, even if there are disorders on one set of chromosomes. One of the chromosomes must be free of defects to ensure health. However, this life-saving heterozygosity could be lost through repeated inbreeding. If, unfortunately, two equally defective chromosomes meet due to mating, we have bred a homozygosity with regard to these genes. In nature, these horses will probably become ill and thus be eliminated from reproduction by natural selection. Other genes are suppressed, some lines die out due to old age or because they are often considered unpopular, and healthy genetic diversity is slowly lost. When the inbreeding level rises to a dangerous level, this can result in both genetic disorders and physical defects.

Fortunately, genetic testing is now widely available. Through education and dissemination of information, WAHO and our breed societies actively encourage testing both stallions and broodmares, with the simple slogan To prevent affected foals, test before you breed.

The next revolution in reproduction technology was the invention of embryo transfer (ET). Within the past twenty-five years or so, ET as a method of breeding has become commonplace practice in many countries. In the earlier years, breeders considered that ET would be helpful in certain rare cases, for example, for an exceptional mare with a medical indication that prevented her from carrying a foal to term herself. Gradually, the popular concept crept in that if stallions could produce multiple foals in a year, then why couldn’t mares do the same.

Valuable mares could carry on with their show or ridden careers while the recipient mare got on with the business of carrying and raising her ET foal. Then breeders realised that they could produce several foals from one mare in one year out of several recipient mares, and thus in theory sell more foals more quickly, as after all, time costs money in the breeding business. Only a small percentage of those multiple ET foals born in the same year will be top quality, and regardless of how they were conceived, there is a limited market for below average foals.

“Only rare things have added value,” said the economist Karl Marx 150 years ago. Producing several siblings in the same year from the same parents makes the foals part of a series and also trivialises the pedigree. What we need is quality, not quantity!

And have we thought enough about the welfare of both the donor and recipient mares during this time? Creating an embryo transfer foal is not that easy. Various veterinary procedures are required, hormones are used to synchronise the donor and recipient mares, with regular internal ultrasound scans. Then, sometimes two, three or more flushings of the uterus are necessary to retrieve a single viable embryo. There is also a health risk to the dam’s uterus and future fertility. It takes a lot of time, a lot of work, a lot of hormone injections and high veterinary costs for each successful ET pregnancy.

Epigenetics involve genetic control influenced by factors other than the horse’s DNA sequence. Epigenetic changes, which can be developmental or environmental, can switch genes on or off and are required for normal development and health. In this case I am referring to the influence of the mares on the foals they give birth to and raise.

A natural daughter or son of the two parents is the so-called A foal. It is the foal that was carried by its own mother. This foal not only carries her DNA, but also her charisma, her character, her movements and everything that the foal receives in utero from the mother mare, who carries it for eleven months, caring for it and educating it for further months until weaning, thus consolidating all these heritable traits.

You could say that an ET foal, i.e. the B or C foal from the same year, has three parents – the genetic sire and dam and the unrelated recipient mare. These foals will be heavily influenced by the mare that actually carries and gives birth to them, in just the same that way foal A is. Many recipient mares are not even Arabians, which can affect the in-utero growth of the foal. This in turn affects their eventual adult height, their limbs in particular, and their movement. The behaviour and temperament of the recipient mare also has a strong influence. Various clinical studies have clearly shown that these epi-genetic changes in humans and animals can be and are passed on to the next generations. I think this is something that would benefit from further research in our Arabians.

Regardless of which artificial method is used to produce the embryo, the greatest risk of changing the Arabian horse breed gradually but fundamentally is the effect of epi-genetics on the development of the foal through recipient mares of a different breed, character and body size.

However, the adoption of the ART method for the reproduction of our horses was not yet complete. The next step was the development of in-vitro reproduction, which also makes use of embryo transfer and is therefore also subject to all the possible risks and side effects, as previously mentioned. For good reasons, the registration of foals produced by any form of in-vitro reproduction is not permitted by WAHO, and all Registries have been asked to add a declaration to foal registration application forms stating this method was not used.

In-vitro reproduction involves removing the oocyte (egg) from the donor mare and placing it in a glass dish in a laboratory. There, the egg to be fertilised is brought together with the sperm. This can either be by ICSI – intracytoplasmic sperm injection – which involves manually selecting a spermatozoon under a microscope and injecting it into the oocyte with a fine needle; or by IVF, in vitro fertilisation. This method involves ovum pick-up, which is the collection of multiple oocytes from the donor mare, which is not a pleasant procedure for her, incubating them with sperm and allowing natural fertilisation to occur without human intervention. Once at the required growth stage, the resulting embryo can then be implanted in a recipient mare, or frozen and stored until it is needed.

Live embryos are then frozen and float by the hundreds in the nitrogen containers of large laboratories or specialised stud farms. Many embryos are full siblings, as the expensive and complex methods are only worthwhile if several embryos can be produced at the same time. In most cases, these embryos are sold at auctions, most likely without declaring the method used to produce them, possibly exported and then used in the recipient mares with all the risks of epi-genetic influence, as already described.

We should ask ourselves what consequences follow from the findings outlined above? How can we better control selection? What trade-offs could be made between ART and the life quality of horses?

Today, after thousands of years, it seems that we have somehow neglected the most important natural reproduction behaviours of our horses, leading to an irresolvable conflict with profit-orientated reproduction technology. Sexual selection by the choosy mares was both the tool and the origin of evolutionary adaptation. It is the adjusting screw that determines the success, health and survival of individuals and species.

The common denominator across all the differences should be our care and support of the horses and the realisation that they only need assisted reproduction in rare cases. This makes it all the more important to honour and preserve healthy Arabian horse breeding in all its natural diversity and sustainability.

For more health features from TheArabianMagazine.Com, click here.

I love this article. Every time I relish the sight of an Arabian stallion or mare I think of these type of things. In short, we MUST make a way for the personality of this breed to thrive despite the technical challenges. I truly wish I too could personally contribute to the spirit of this majestic creature. If I could lasso the simple love I’ve possessed since a child…..